On the 27 April, 1916, a shell fired from the Helga set alight a barricade on Lower Abbey Street. The blaze spread along the street, engulfing the premises of the Royal Hibernian Academy (RHA), then hosting its Annual Exhibition. Over five hundred works of art were on display, all of which were destroyed, along with the Academy’s holdings of fine art prints, books, and other materials. Claims by the Academy and its artists in the Property Losses (Ireland) Committee (PLIC) archive are vital documents in which the material world of the early twentieth-century Academy is captured, evoking the artistic milieu to be found in Dublin at this time. In his afterword to the recent publication, Making 1916: Material and Visual Culture of the Easter Rising, Nicholas Allen noted that ‘if the archive represents a material repository of historical experience, then the history of lost or destroyed objects, as may be recovered only in memory or in fragments, is imaginable in a language of sensation.’[1] This sensory world, conjured up by the descriptions of furniture, textiles and artworks are not only records of what was lost, but a reminder of the connections between Dublin and a global artistic economy. In addition to the property and goods owned by the RHA itself, the paintings lost to the flames also reflect the multifaceted interests and lives of the exhibitors: while all broadly academic rather than modernist in artistic technique, the different claims show that artists connected to empire, to the nationalist movement, those displaced by the First World War, collectors and enthusiastic amateurs, were brought together in the broad church of the Annual Exhibition.

In contrast to the well-known, black and white image of the ruined Academy, the list of furnishings offers a sense of a colourful, and comfortable, interior. Built in 1824, and designed by Francis Johnston (the first President of the RHA), the building was typically elegant and classically proportioned. In the lobby, visitors were greeted across a leather-topped mahogany table, while in the Secretary’s office, stationary was kept in a ‘solid old Sau Domingo’ cupboard. The exhibition rooms, the claim tells us, were furnished with crimson door hangings, the floors covered by two large Turkish carpets, while the smaller public areas were carpeted in red baize. A ten foot high ‘collapsible rolling platform with adjustable ladder’ placed the pictures at every available space along the walls, while smaller works were displayed on screens, some of which were covered in cloth. Other works, such as miniatures, were displayed in a mahogany glass case, and up to twenty-four sculptures could be placed on exhibition pedestals. Four ottomans, upholstered and stuffed, offered a resting place for visitors to the exhibition.

In contrast to the well-known, black and white image of the ruined Academy, the list of furnishings offers a sense of a colourful, and comfortable, interior. Built in 1824, and designed by Francis Johnston (the first President of the RHA), the building was typically elegant and classically proportioned. In the lobby, visitors were greeted across a leather-topped mahogany table, while in the Secretary’s office, stationary was kept in a ‘solid old Sau Domingo’ cupboard. The exhibition rooms, the claim tells us, were furnished with crimson door hangings, the floors covered by two large Turkish carpets, while the smaller public areas were carpeted in red baize. A ten foot high ‘collapsible rolling platform with adjustable ladder’ placed the pictures at every available space along the walls, while smaller works were displayed on screens, some of which were covered in cloth. Other works, such as miniatures, were displayed in a mahogany glass case, and up to twenty-four sculptures could be placed on exhibition pedestals. Four ottomans, upholstered and stuffed, offered a resting place for visitors to the exhibition.

The Council Chamber was equally well appointed: the floors covered with a Turkish carpet and hearth rug, a twelve-foot long mahogany Council table, around which twenty-two mahogany chairs with velvet cushions were gathered. Additional furniture included a mahogany portfolio stand, along with glazed cases for storing books, engravings and antiquities. The ‘glazed book cases’ and ‘glazed engravings cabinets’ held a wealth of art history and fine art publications. Among the losses were eight folios of Goya’s ‘Disasters of War’, presented by the Spanish Government, two folios of Piranesi’s Roman antiquities, a bound folio of etchings by Bartolozzi after Guercino, and a set of mezzotints of English landscapes by Constable, which had been presented by the artist. The claim also mentions ‘several portfolios of etchings and engravings’, by artists such as Dürer, Ostade, Canaletto, and Tiepolo, and ‘numerous drawings by old masters’. Significant publications included Gilbert’s History of Dublin, ‘High Crosses of Ireland’ by Henry O’Neill, as well as texts by John Ruskin and Joshua Reynolds. As the RHA Drawing Schools were located on-site, a long list of art materials was also lost, including easels, stools, ‘mattresses for the model posing, draperies, costumes etc’, a ‘mounted and articulated male skeleton in glass’, and a series of plaster casts after antique sculpture.[2]

The RHA Council decided that individual artists would make their own claims to the PLIC. As the archive shows, few artists received the full amount that they claimed for, often resulting in a series of letters between the different parties. The records shed light on a number of artists (many of whom were female) who are not known today. Among these, Norah M O’Kelly presents an intriguing case. In 1916, she submitted four oil paintings to the RHA, all showing landscape views of places in India – two of Calcutta (now Kolkata), one of Darjeeling, and one titled ‘A Quiet Grave in the Himalayas’. The claim for £22 7s was submitted by Norah’s father, Bernard O’Kelly, as his daughter was then resident in India. Her address, given as ‘Loreto House, 7 Middleton Row, Calcutta’, was (and remains to this day) a school founded in 1840 by a group of seven Loreto sisters and five postulates from Ireland. The 1911 Census reveals that Norah was an art teacher in her twenties, and her artistic training is confirmed by the records of the Dublin Metropolitan School of Art. Her father’s letter to the PLIC notes that she ‘was very anxious to sell’ her works at the RHA, and that they had been priced with this in mind. While more research is needed to find out why O’Kelly was in India, her presence there adds to the myriad connections between the two countries at that time.

Three Belgian refugees exhibited work at the 1916 exhibition: Edmund Delrenne, Marthe Donas, and Théophile Nicolet. Delrenne and Donas had both exhibited work at the 1915 Annual Exhibition, proceeds of which went to the Belgian Relief Fund. Delrenne was resident in Dublin at the time of the Rising, and his paintings of the destroyed city are among the few works by visual artists made on the subject at the time.[3] Although Donas exhibited from addresses in Dublin (Fitzwilliam Square in 1915, and Leeson Street in 1916), by the time she submitted her claim, she was living in Eastbourne, Sussex. Recent research on Donas’ life and career reveals that by the end of 1916, she was living in Paris and early in 1917 was a student of Andre Lhote – later teacher of Maine Jellett and Evie Hone.[4] In a separate claim, Dermod O’Brien PRHA noted that a framed etching was also among the Academy’s losses.[5] Nicolet does not seem to have been resident in Ireland, but sent works to the RHA from 1913 onwards. At this date, the artist was living in Bruges, but by 1915, had moved to France. According to a letter included in the claim file, Irish artist Kathleen Fox had encouraged Nicolet to exhibit in Dublin. In the paperwork, Nicolet identified himself as ‘a Belgian refugee at Pont Aven /Finstere, France’. [6] It is possible that Fox had come into contact with Nicolet during her time in Europe prior to the outbreak of war. Given the large number of Irish artists who studied in Antwerp in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, it is also possible that they were connected through this network.

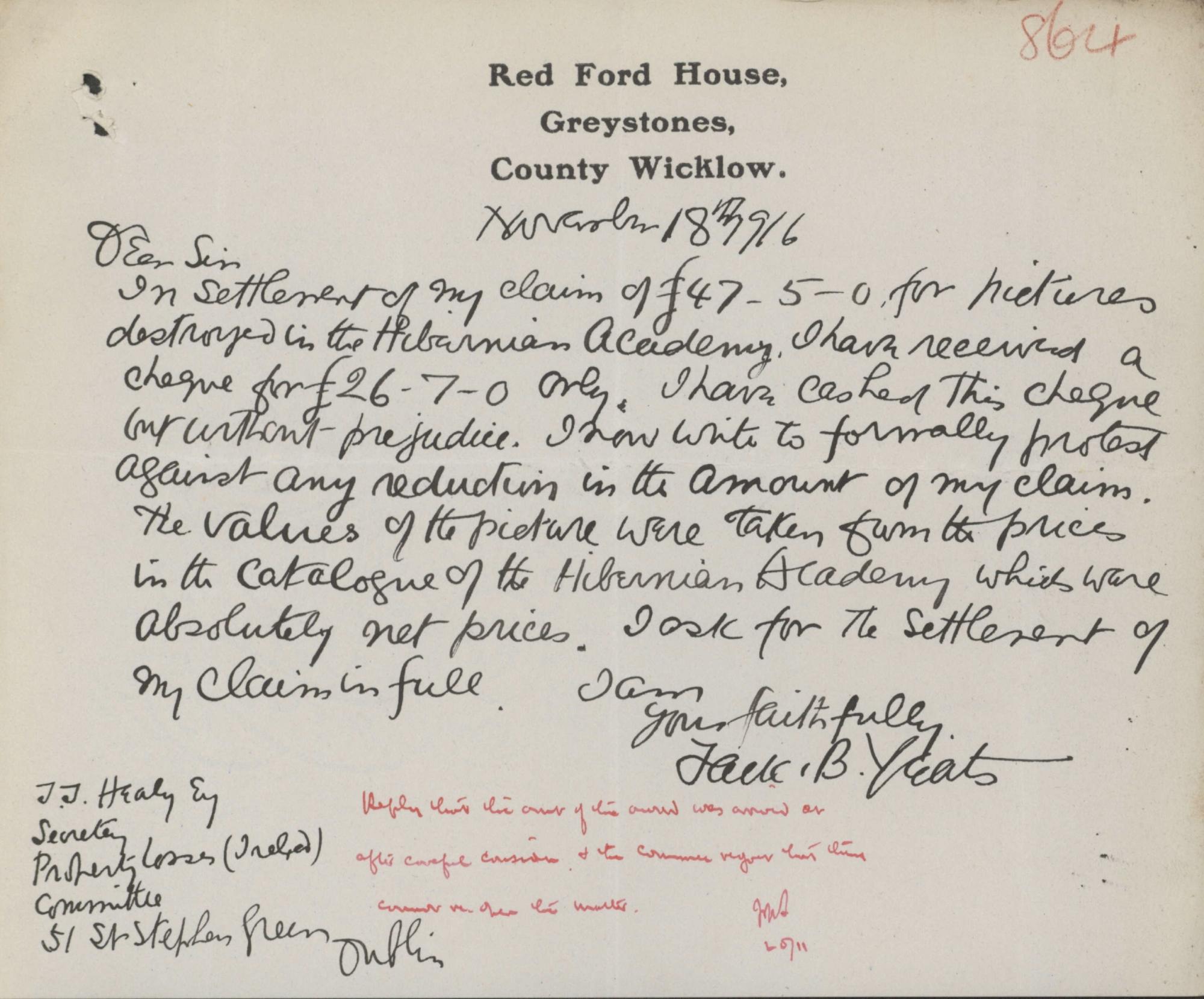

Among the more familiar names exhibiting at the RHA in 1916 were Margaret Clarke, Sarah Purser, James Sleator, and Jack B Yeats. These artists are representative of the main strands in Irish painting in the early-twentieth century. Born in Newry and Portadown respectively, Clarke and Sleator had trained with William Orpen at the Dublin Metropolitan School of Art, and his influence was noticeable in their work. Clarke submitted a claim of £60 for two subject pictures. In response to a letter from the artist, O’Brien noted that her pictures ‘were worth the very modest sums you put on them’, however she only received £30 12s in compensation.[7] Sleator was awarded £127 10s for five paintings (which he had valued at £405, including frames), including a portrait of Lennox Robinson.[8] Purser claimed for seven works, predominantly portraits,[9] while Yeats submitted a claim of £47 5s for three oil paintings: ‘The Donkey Show’, ‘The Turning Point in the Tide’, and ‘The Runaway’. Dissatisfied with the £26 7s he received, Yeats wrote to the committee to ‘formally protest against any reduction in the amount’, and requested a full settlement. [10] Yeats also lost work in another fire on Middle Abbey Street, at the premises of the publishers Maunsel & Company – as did Harry Clarke, along with several other artists and writers.

A series of claims from artists based around Britain were managed by the Imperial Arts League (IAL).[11] Founded in London in 1909, the League advocated for contemporary artists, and looked after legal issues, insurance, copyright and other aspects of art business. The Director of the National Museum in Dublin, Count Plunkett, sat on the committee, along with other museum professionals and artists. The IAL submitted sixteen claims on behalf of its members, including Norman Garstin and John Lavery, both of whom had Irish connections. While the involvement of Irish-born (or resident) artists in the League has yet to be researched, its presence in this archive is a reminder of the connections, both institutional and personal, that criss-crossed over the Irish Sea.

The PLIC claims of the Royal Hibernian Academy and its exhibitors are a key to opening up the lost exhibition of 1916: through lists and descriptions, the letters of artists, their families (and on occasion their solicitors). The colour and texture of the Academy building, along with the ghosts of the lost images, begin to re-emerge in these documents. They reveal the network of artistic connections and exchange that spread out from Dublin, around Ireland, to London, Pont Aven, and beyond. Thomas Pugh, who fought with the rebels at Jacob’s Biscuit Factory, later recalled that on Saturday, 23 April, he ‘went into town and went to an exhibition of pictures, in the Royal Hibernian Academy. I was the last man to leave the exhibition.’[12] Pugh was surely among the last members of the public to view the exhibition prior to its destruction, and is a corporeal link between the city, the Academy, and the Easter Rising.

About the author: Dr. Kathryn Milligan is the inaugural ESB Fellow at the ESB Centre for the Study of Irish Art, at the National Gallery of Ireland. She received her doctorate from Trinity College Dublin in 2015, where her thesis examined the depiction of Dublin in visual art in the period 1850 – 1950; this study is now being prepared for publication. Dr. Milligan is also Chair of the Irish Association of Art Historians, and her recent publications include ‘Edmond Delrenne: Witness to 1916’ (Irish Arts Review, Winter 2015).

[1] Nicholas Allen, Afterword, ‘Lost city of the archipelago: Dublin at the end of empire’, Making 1916: Material and Visual Culture of the Easter Rising, edited by Lisa Godson and Joanna Brück, (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2015). 262.

[2] All details of the RHA furnishing and contents are found in PLIC/1/6267.

[3] PLIC/1/3294.

[4] PLIC/1/2627. See Peter J H Pauwels and Kristen Boon, Marthe Donas: A Woman Artist in the Avant-Garde (Netherlands: Ludion, 2016).

[5] PLIC/1/624.

[6] PLIC/1/6839.

[7] PLIC/1/77.

[8] PLIC/1/618.

[9] PLIC/1/588.

[10] PLIC/1/738.

[11] For IAL correspondence see PLIC/1/1224, PLIC/1/1394, and PLIC/1/1225.

[12] Thomas Pugh, Bureau of Military History Witness Statement No 397.