Dr. William Murphy, lecturer at the School of History and Geography, Dublin City University, outlines the history behind the establishment of a detention camp for Irish rebels in the rural village of Frongoch in north Wales, and explores the stories of some of the men held there.

Published: December 6, 2016

This series of exhibitions has been made possible through generous support from the Reconciliation Fund of the Irish Government's Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade

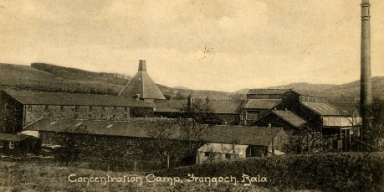

In 1916, quite suddenly, Frongoch entered Irish history. It was then a remote country place in north Wales with little to offer but natural beauty, unreliable weather, its location on the railway line from Bala to Ffestiniog, and a collection of buildings that had been a distillery once. Taken together however, the isolation, the railway and the distillery buildings, if not the weather, provided the foundations for a prison camp. And it was to that camp that a group of Irish prisoners arrived by train on 9 June. Many more followed during the succeeding weeks till, at the end of that month, they numbered 1,775.

Frongoch could accommodate so many so quickly because the Irish prisoners were not the first. The War Office had opened the camp in 1914 as a ‘Lager Fuer Kriegsgefangene’ to hold German prisoners-of-war. In doing so they had, in fact, created two camps: a south camp in the converted distillery and a north camp consisting of twenty-seven large huts. Both combined dormitories with other essential facilities. The Germans were rather hurriedly evacuated when the British authorities – taken by surprise and improvising – decided that Frongoch was the most suitable available location to congregate and detain the majority of the men arrested in the aftermath of Ireland’s Easter Rising.

For most of those men Frongoch was the end of the line, the last link in the carceral chain. They had been swept up in the days and weeks following the outbreak of the Rising, when the military in Ireland arrested as many as 3,500 people. The army, assisted by the police, had begun with rebels, based for the most part in Dublin, but had moved on to suspected sympathizers, many of them from places that had been undisturbed by the trouble. In doing so they filled up Ireland’s barracks, prisons and, during the initial chaos, makeshift places of detention like the cattle pens at the Royal Dublin Society’s showgrounds.

Even as the suspects were gathered in, the task of processing those first arrested had begun. Initially, fifteen leaders and, later, Roger Casement were executed. One woman and 140 men were sentenced to convict prisons following courts martial. The men were sent to Dartmoor and Portland prisons, while Constance Markievicz’s destination was Aylesbury prison. Finally, according to Seán McConville, 2,519 suspects were deported to Britain for internment without trial.

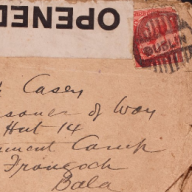

Robert Holland was one of these. He had fought at the Marrowbone Lane Distillery, near the South Dublin Union, and on surrender was brought to Richmond Barracks. In the weeks after the Rising it acted as an over-crowded clearing-house. There some of the potential internees were released, having been identified as arrested in error or comparatively harmless. The rest, like Holland, were dispatched in batches to Dublin port and onward to Britain. Once there, five women were held at Lewes prison while the interned men were at first scattered to eight prisons and detention centres. Holland was among a group sent to Knutsford prison, Chesire, in early May. During this short phase, when the regimes in Knutsford and elsewhere were harsh, some further internees were released while a very small number were identified as leaders. In June that elite was sent to Reading Gaol when the majority, including Holland, was sent to Frongoch. At Reading and Frongoch the conditions were better, the internees had more control over their lives, and they experienced the pleasure of making new friends, though, of course, they remained prisoners.

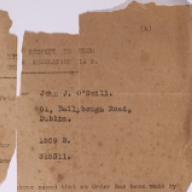

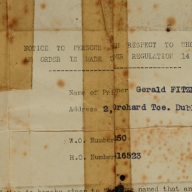

As Holland’s internment order shows, they were detained there under Regulation 14B of the Defence of the Realm Act. This war-time regulation had been designed to facilitate the internment of ‘alien internees’, Germans and Austrians living in the United Kingdom, on the grounds that their ‘hostile origins or associations’ posed a threat. In mid-May, at the suggestion of officials at the Home Office, the cabinet concluded that this regulation provided the simplest way to make legal the ongoing internment of those associated with the Irish Rising. Given the ‘known connection of Sinn Féin to Germany’, and the rebel proclamation’s reference to ‘our gallant allies in Europe’, the men could, the authorities agreed, be regarded as having ‘hostile associations’. Legally, that is the key phrase in Holland’s, and all the others’, internment orders. The rest, even if it was underlined, was mere detail.

While home to the Irish, Frongoch, just like the camps for alien internees, was administered by the Home Office and staffed by army personnel. As one of the internees, Thomas Pugh, realized, ‘we were nobody’s children, we were neither prisoners of war nor convicts and they did not know what to do with us.’ Reflecting this ambiguous status, each man was assigned both a ‘W.O. Number’ and a ‘H.O. Number’ on their internment order: Holland’s were respectively, as you can see, 1267E and 315385.

As Holland’s internment order also illustrates, each individual held under Regulation 14B was entitled to have his or her case reviewed by an ‘Advisory Committee’. The body that had examined the cases of alien internees, under the chairmanship of Sir John Sankey, was also assigned the task of the Irish internees. To assist in this Jonathan Pim, a former attorney general of Ireland, was added to the committee ‘so that it should not be said that Irishmen were being tried by an almost wholly English tribunal.’ As it was unlikely that many of the Irish internees would submit an appeal, it was decided to review all the cases. During twenty-five days of hearings the advisory committee interviewed all 1,846 internees who remained in custody. Sankey described it as ‘one of the hardest and certainly the most disagreeable job I have ever done’ but by late August he had recommended the release of 1,273 (69%) of the internees.

In September, because of these releases, the population of Frongoch fell to about 540 men. Around the same time relations between the internees and the camp authorities, in particular the camp commandant, Colonel F.A. Heygate Lambert, deteriorated. This development had several roots. Men who were among the most radical and aggressive of the original internees dominated the reduced cohort. As importantly, they had become both more organized over time and increasingly disgruntled at their incarceration while they were encouraged to protest by the emergence of prisoner support groups outside. Further, the internees’ irritation was exacerbated by two policies pursued by the authorities. First, they began to demand from the internees work that did not relate directly to maintaining themselves in the camp. Second, they attempted, at the request of the War Office, to remove a number of internees who were liable for conscription under the Military Service Act of January 1916. That Act had declared that any unmarried male British subject between the ages of 18 and 41, who was ‘ordinarily resident in Great Britain’ on 15 August 1915, was liable for military service. This was true of a small but significant group of men in Frongoch, including Michael Collins who had been working in London in August 1915.

A large proportion, though not all, of the internees responded by refusing to do the work or to identify the men sought for conscription, leading to significant conflict inside the camp. Communicating through the most important prisoner support group, the Irish National Aid and Volunteer Dependants’ Fund (INA&VDF), the internees publicized what they regarded as this ill-treatment. The highly propagandistic Official Report of the Ill-Treatment of the Irish Prisoners of War, published by the INA&VDF in Cork is an example of this.

As public discontent around the ongoing internments grew in Ireland, John Redmond became evermore wary of the dangers for the Irish Party. On 30 November he appealed to Prime Minister, H. H. Asquith, arguing that the Irish public expected a general release and warning that if ‘popular expectations are disappointed, the result will be a fresh outbreak of bitterness and exasperation’. If the internees were not released now, he continued, they would be released after ‘months of furious and angry agitation . . . when infinite mischief has been done’. Much mischief had already been done: not only had general resentment been stoked in nationalist Ireland, influential new networks of activists had been created inside the camp and in the support organizations, and the first signs of effective prison protest strategies had emerged.

Three weeks later, on 21 December, the new Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, decided that freeing these men was, on balance, likely to cause less trouble than keeping them at Frongoch. The remaining female internees, then at Aylesbury, were also freed. In an attempt to minimize demonstrations of support, their releases were staggered over the next few days, but two internees remained in Wales that Christmas. William Thomas Halpin and Edward Tierney were by then inmates of Denbeigh asylum for the insane. During the months that followed two local women continued to visit them, while Art O’Brien, the chief mover in a London-based prisoner support group called the Irish National Relief Fund, lobbied for their removal to other hospitals, closer to their relatives. In April, Tierney was transferred to Long Grove Asylum in Epsom, near London, and finally released on 16 November 1917. Halpin was transferred to Grangegorman Asylum in Dublin where he lived until 1925; following his death that year he was interred in the republican plot in Glasnevin cemetery.

Further Reading:

Lyn Ebenezer, Fron-goch and the birth of the IRA (Llanrwst, 2006).

Seán McConville, Irish Political Prisoners, 1848-1922: Theatres of War (London, 2003).

William Murphy, Political Imprisonment and the Irish, 1912-1921 (Oxford, 2014).

Seán O’Mahony, Frongoch: University of Revolution (Dublin, 1987).

Author Biography

Dr William Murphy is a lecturer at the School of History and Geography, Dublin City University. He is the author of Political Imprisonment and the Irish, 1912-1921 (Oxford University Press, 2014), which is now available in paperback. Currently, William is one of the team working on the Wellcome Trust funded project 'Prisoners, Medical Care, and Entitlement to Health in England and Ireland, 1850-2000'. To learn more about that project visit https://